Shor's algorithm

Shor's algorithm, named after mathematician Peter Shor, is a quantum algorithm (an algorithm which runs on a quantum computer) for integer factorization formulated in 1994. Informally it solves the following problem: Given an integer N, find its prime factors.

On a quantum computer, to factor an integer N, Shor's algorithm runs in polynomial time (the time taken is polynomial in log N, which is the size of the input).[1] Specifically it takes time O((log N)3), demonstrating that the integer factorization problem can be efficiently solved on a quantum computer and is thus in the complexity class BQP. This is exponentially faster than the most efficient known classical factoring algorithm, the general number field sieve, which works in sub-exponential time -- about O(e1.9 (log N)1/3 (log log N)2/3)(http://mathworld.wolfram.com/NumberFieldSieve.html). The efficiency lies in the efficiency of the quantum Fourier transform, and modular exponentiation by squarings.

Given a quantum computer with a sufficient number of qubits, Shor's algorithm can be used to break public-key cryptography schemes such as the widely used RSA scheme. RSA is based on the assumption that factoring large numbers is computationally infeasible. So far as is known, this assumption is valid for classical (non-quantum) computers; no classical algorithm is known that can factor in polynomial time. However, Shor's algorithm shows that factoring is efficient on a quantum computer, so an appropriately large quantum computer can break RSA. It was also a powerful motivator for the design and construction of quantum computers and for the study of new quantum computer algorithms. It has also facilitated research on new cryptosystems that are secure from quantum computers, collectively called post-quantum cryptography.

In 2001, Shor's algorithm was demonstrated by a group at IBM, who factored 15 into 3 × 5, using an NMR implementation of a quantum computer with 7 qubits.[2] However, some doubts have been raised as to whether IBM's experiment was a true demonstration of quantum computation, since no entanglement was observed.[3] Since IBM's implementation, several other groups have implemented Shor's algorithm using photonic qubits, emphasizing that entanglement was observed.[4][5]

Contents |

Procedure

The problem we are trying to solve is: given an odd composite number  , find an integer

, find an integer  , strictly between 1 and

, strictly between 1 and  , that divides

, that divides  . We are interested in odd values of

. We are interested in odd values of  because any even value of

because any even value of  trivially has the number 2 as a prime factor. We can use a primality testing algorithm to make sure that

trivially has the number 2 as a prime factor. We can use a primality testing algorithm to make sure that  is indeed composite.

is indeed composite.

Moreover, for the algorithm to work, we need  not to be the power of a prime. This can be tested by taking square, cubic, ...,

not to be the power of a prime. This can be tested by taking square, cubic, ...,  -roots of

-roots of  , for

, for  , and checking that none of these is an integer. (This actually excludes that

, and checking that none of these is an integer. (This actually excludes that  for some integer

for some integer  and

and  .)

.)

Since  is not a power of a prime, it is the product of two coprime numbers greater than 1. As a consequence of the Chinese remainder theorem, 1 has at least four distinct roots modulo

is not a power of a prime, it is the product of two coprime numbers greater than 1. As a consequence of the Chinese remainder theorem, 1 has at least four distinct roots modulo  , two of them being 1 and

, two of them being 1 and  . The aim of the algorithm is to find a square root

. The aim of the algorithm is to find a square root  of 1, other than 1 and

of 1, other than 1 and  ; such a

; such a  will lead to a factorization of

will lead to a factorization of  , as in other factoring algorithms like the quadratic sieve.

, as in other factoring algorithms like the quadratic sieve.

In turn, finding such a  is reduced to finding an element

is reduced to finding an element  of even period with a certain additional property (as explained below, it is required that the condition of Step 6 of the classical part does not hold). The quantum algorithm is used for finding the period of randomly chosen elements

of even period with a certain additional property (as explained below, it is required that the condition of Step 6 of the classical part does not hold). The quantum algorithm is used for finding the period of randomly chosen elements  , as order-finding is a hard problem on a classical computer.

, as order-finding is a hard problem on a classical computer.

Shor's algorithm consists of two parts:

- A reduction, which can be done on a classical computer, of the factoring problem to the problem of order-finding.

- A quantum algorithm to solve the order-finding problem.

Classical part

- Pick a random number a < N

- Compute gcd(a, N). This may be done using the Euclidean algorithm.

- If gcd(a, N) ≠ 1, then there is a nontrivial factor of N, so we are done.

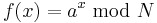

- Otherwise, use the period-finding subroutine (below) to find r, the period of the following function:

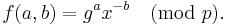

,

,

of

of  in

in  , which is the smallest positive integer r for which

, which is the smallest positive integer r for which

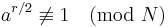

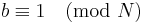

- If r is odd, go back to step 1.

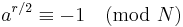

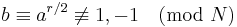

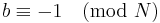

- If a r /2 ≡ −1 (mod N), go back to step 1.

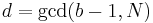

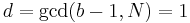

- gcd(ar/2 ± 1, N) is a nontrivial factor of N. We are done.

Quantum part: Period-finding subroutine

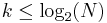

The quantum circuits used for this algorithm are custom designed for each choice of N and the random a used in f(x) = ax mod N. Given N, find Q = 2q such that  , which implies

, which implies  . The input and output qubit registers need to hold superpositions of values from 0 to Q − 1, and so have q qubits each. Using what might appear to be twice as many qubits as necessary guarantees that there are at least N different x which produce the same f(x), even as the period r approaches N/2.

. The input and output qubit registers need to hold superpositions of values from 0 to Q − 1, and so have q qubits each. Using what might appear to be twice as many qubits as necessary guarantees that there are at least N different x which produce the same f(x), even as the period r approaches N/2.

Proceed as follows:

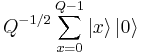

- Initialize the registers to

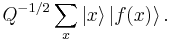

- Construct f(x) as a quantum function and apply it to the above state, to obtain

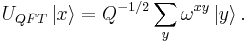

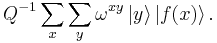

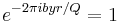

- Apply the quantum Fourier transform to the input register. This transform (operating on a superposition of power-of-two Q = 2q states) uses a Qth root of unity such as

to distribute the amplitude of any given

to distribute the amplitude of any given  state equally among all Q of the

state equally among all Q of the  states, and to do so in a different way for each different x:

states, and to do so in a different way for each different x:

can be factored out whenever x0 and x produce the same value. Let

can be factored out whenever x0 and x produce the same value. Let

be a Qth root of unity,

be a Qth root of unity,- r be the period of f,

- x0 be the smallest of a set of x which yield the same given f(x) (we have x0 < r), and

- b run from 0 to

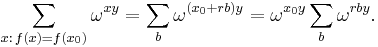

so that

so that

is a unit vector in the complex plane (

is a unit vector in the complex plane ( is a root of unity and r and y are integers), and the coefficient of

is a root of unity and r and y are integers), and the coefficient of  in the final state is

in the final state is

point in nearly the same direction in the complex plane, which requires that

point in nearly the same direction in the complex plane, which requires that  point along the positive real axis.

point along the positive real axis. - Perform a measurement. We obtain some outcome y in the input register and

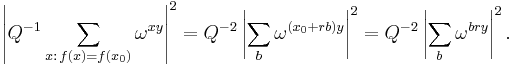

in the output register. Since f is periodic, the probability of measuring some pair y and

in the output register. Since f is periodic, the probability of measuring some pair y and  is given by

is given by

is to the positive real axis, or the closer yr/Q is to an integer.Unless r is a power of 2, it won't be a factor of Q.

is to the positive real axis, or the closer yr/Q is to an integer.Unless r is a power of 2, it won't be a factor of Q. - Perform Continued Fraction Expansion on y/Q to make an approximation of it, and produce some c/r′ by it that satisfies two conditions:

- A: r′<N

- B: |y/Q - c/r′| < 1/2Q.

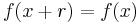

- Check if f(x) = f(x + r′)

If so, we are done.

If so, we are done. - Otherwise, obtain more candidates for r by using values near y, or multiples of r′. If any candidate works, we are done.

- Otherwise, go back to step 1 of the subroutine.

Explanation of the algorithm

The algorithm is composed of two parts. The first part of the algorithm turns the factoring problem into the problem of finding the period of a function, and may be implemented classically. The second part finds the period using the quantum Fourier transform, and is responsible for the quantum speedup.

I. Obtaining factors from period

The integers less than N and coprime with N form a finite Abelian group  under multiplication modulo N. The size is given by Euler's totient function

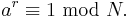

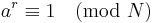

under multiplication modulo N. The size is given by Euler's totient function  . By the end of step 3, we have an integer a in this group. Since the group is finite, a must have a finite order r, the smallest positive integer such that

. By the end of step 3, we have an integer a in this group. Since the group is finite, a must have a finite order r, the smallest positive integer such that

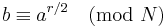

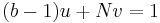

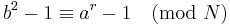

Therefore, N divides (also written | ) a r − 1 . Suppose we are able to obtain r, and it is even. (If r is odd, see step 5.) Now  is a square root of 1 modulo

is a square root of 1 modulo  , different from 1. This is because

, different from 1. This is because  is the order of

is the order of  modulo

modulo  , so

, so  . If

. If  , by step 6 we have to restart the algorithm with a different random number

, by step 6 we have to restart the algorithm with a different random number  .

.

Eventually, we must hit an  , of order

, of order  in

in  , such that

, such that  . This is because such a

. This is because such a  is a square root of 1 modulo

is a square root of 1 modulo  , other than 1 and

, other than 1 and  , whose existence is guaranteed by the Chinese remainder theorem, since

, whose existence is guaranteed by the Chinese remainder theorem, since  is not a prime power.

is not a prime power.

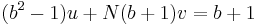

We claim that  is a proper factor of

is a proper factor of  , that is,

, that is,  . In fact if

. In fact if  , then

, then  divides

divides  , so that

, so that  , against the construction of

, against the construction of  . If on the other hand

. If on the other hand  , then by Bézout's identity there are integers

, then by Bézout's identity there are integers  such that

such that

.

.

Multiplying both sides by  we obtain

we obtain

.

.

Since  divides

divides  , we obtain that

, we obtain that  divides

divides  , so that

, so that  , again contradicting the construction of

, again contradicting the construction of  .

.

Thus  is the required proper factor of

is the required proper factor of  .

.

II. Finding the period

Shor's period-finding algorithm relies heavily on the ability of a quantum computer to be in many states simultaneously. Physicists call this behavior a "superposition" of states. To compute the period of a function f, we evaluate the function at all points simultaneously.

Quantum physics does not allow us to access all this information directly, though. A measurement will yield only one of all possible values, destroying all others. But for the no cloning theorem, we could first measure f(x) without measuring x, and then make a few copies of the resulting state (which is a superposition of states all having the same f(x)). Measuring x on these states would provide different x values which give the same f(x), leading to the period. Because we cannot make exact copies of a quantum state, this method does not work. Therefore we have to carefully transform the superposition to another state that will return the correct answer with high probability. This is achieved by the quantum Fourier transform.

Shor thus had to solve three "implementation" problems. All of them had to be implemented "fast", which means that they can be implemented with a number of quantum gates that is polynomial in  .

.

- Create a superposition of states. This can be done by applying Hadamard gates to all qubits in the input register. Another approach would be to use the quantum Fourier transform (see below).

- Implement the function f as a quantum transform. To achieve this, Shor used repeated squaring for his modular exponentiation transformation. It is important to note that this step is more difficult to implement than the quantum Fourier transform, in that it requires ancillary qubits and substantially more gates to accomplish.

- Perform a quantum Fourier transform. By using controlled rotation gates and Hadamard gates Shor designed a circuit for the quantum Fourier transform (with Q = 2q) that uses just

gates.[6]

gates.[6]

After all these transformations a measurement will yield an approximation to the period r. For simplicity assume that there is a y such that yr/Q is an integer. Then the probability to measure y is 1. To see that we notice that then

for all integers b. Therefore the sum whose square gives us the probability to measure y will be Q/r since b takes roughly Q/r values and thus the probability is  . There are r y such that yr/Q is an integer and also r possibilities for

. There are r y such that yr/Q is an integer and also r possibilities for  , so the probabilities sum to 1.

, so the probabilities sum to 1.

Note: another way to explain Shor's algorithm is by noting that it is just the quantum phase estimation algorithm in disguise.

Discrete logarithms

Suppose we know that  , for some r, and we wish to compute r, which is the discrete logarithm:

, for some r, and we wish to compute r, which is the discrete logarithm:  . Consider the Abelian group

. Consider the Abelian group  where each factor corresponds to modular multiplication of nonzero values, assuming p is prime. Now, consider the function

where each factor corresponds to modular multiplication of nonzero values, assuming p is prime. Now, consider the function

This gives us an Abelian hidden subgroup problem, as f corresponds to a group homomorphism. The kernel corresponds to modular multiples of (r,1). So, if we can find the kernel, we can find r

In popular culture

On the television show Stargate Universe, the lead scientist, Dr. Nicholas Rush, hoped to use Shor's algorithm to crack Destiny's master code. He taught a quantum cryptography class at the University of California, Berkeley, in which Shor's algorithm was studied.[7]

Shor's algorithm was also a correct answer to a question in a Physics Bowl competition on the television show The Big Bang Theory.

References

- ^ See also Pseudo-polynomial time.

- ^ Vandersypen, Lieven M. K.; Steffen, Matthias; Breyta, Gregory; Yannoni, Costantino S.; Sherwood, Mark H. & Chuang, Isaac L. (2001), "Experimental realization of Shor's quantum factoring algorithm using nuclear magnetic resonance" (PDF), Nature 414 (6866): 883–887, arXiv:quant-ph/0112176, Bibcode 2001Natur.414..883V, doi:10.1038/414883a, PMID 11780055, http://cryptome.org/shor-nature.pdf

- ^ Braunstein, S. L.; Caves, C. M.; Jozsa, R.; Linden, N.; Popescu, S.; Schack, R. (1999), "Separability of Very Noisy Mixed States and Implications for NMR Quantum Computing", Phys. Rev. Lett 83 (5): 1054–1057, arXiv:quant-ph/9811018, Bibcode 1999PhRvL..83.1054B, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.1054

- ^ Lu, Chao-Yang; Browne, Daniel E.; Yang, Tao & Pan, Jian-Wei (2007), "Demonstration of a Compiled Version of Shor's Quantum Factoring Algorithm Using Photonic Qubits", Physical Review Letters 99 (25): 250504, Bibcode 2007PhRvL..99y0504L, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.250504

- ^ Lanyon, B. P.; Weinhold, T. J.; Langford, N. K.; Barbieri, M.; James, D. F. V.; Gilchrist, A. & White, A. G. (2007), "Experimental Demonstration of a Compiled Version of Shor's Algorithm with Quantum Entanglement", Physical Review Letters 99 (25): 250505, Bibcode 2007PhRvL..99y0505L, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.250505

- ^ Shor 1999, p. 14.

- ^ http://stargate.wikia.com/wiki/Shor%27s_algorithm

Further reading

- Nielsen, Michael A. & Chuang, Isaac L. (2000), Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, Cambridge University Press.

- Phillip Kaye, Raymond Laflamme, Michele Mosca, An introduction to quantum computing, Oxford University Press, 2007, ISBN 019857049X

- "Explanation for the man in the street" by Scott Aaronson, "approved" by Peter Shor. (Shor wrote "Great article, Scott! That’s the best job of explaining quantum computing to the man on the street that I’ve seen."). Scott Aaronson suggests the following 12 references as further reading (out of "the 10105000 quantum algorithm tutorials that are already on the web."):

- Shor, Peter W. (1997), "Polynomial-Time Algorithms for Prime Factorization and Discrete Logarithms on a Quantum Computer", SIAM J. Comput. 26 (5): 1484–1509, arXiv:quant-ph/9508027v2, Bibcode 1999SIAMR..41..303S, doi:10.1137/S0036144598347011. Revised version of the original paper by Peter Shor ("28 pages, LaTeX. This is an expanded version of a paper that appeared in the Proceedings of the 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, Santa Fe, NM, Nov. 20--22, 1994. Minor revisions made January, 1996").

- Quantum Computing and Shor's Algorithm, Matthew Hayward, 2005-02-17, imsa.edu, LaTeX2HTML version of the original 2750 line LaTeX document, also available as a 61 page PDF or postscript document.

- Quantum Computation and Shor's Factoring Algorithm, Ronald de Wolf, CWI and University of Amsterdam, January 12, 1999, 9 page postscript document.

- Shor's Factoring Algorithm, Notes from Lecture 9 of Berkeley CS 294-2, dated 4 Oct 2004, 7 page postscript document.

- Chapter 6 Quantum Computation, 91 page postscript document, Caltech, Preskill, PH229.

- Quantum computation: a tutorial by Samuel L. Braunstein.

- The Quantum States of Shor's Algorithm, by Neal Young, Last modified: Tue May 21 11:47:38 1996.

- A now-circular reference via the Wikipedia copy of this article; clearly Aaronson's link originally reached the February 20, 2007 version.

- III. Breaking RSA Encryption with a Quantum Computer: Shor's Factoring Algorithm, Lecture notes on Quantum computation, Cornell University, Physics 481-681, CS 483; Spring, 2006 by N. David Mermin. Last revised 2006-03-28, 30 page PDF document.

- arXiv quant-ph/0303175 Shor's Algorithm for Factoring Large Integers. C. Lavor, L.R.U. Manssur, R. Portugal. Submitted on 29 Mar 2003. This work is a tutorial on Shor's factoring algorithm by means of a worked out example. Some basic concepts of Quantum Mechanics and quantum circuits are reviewed. It is intended for non-specialists which have basic knowledge on undergraduate Linear Algebra. 25 pages, 14 figures, introductory review.

- arXiv quant-ph/0010034 Shor's Quantum Factoring Algorithm, Samuel J. Lomonaco, Jr, Submitted October 9, 2000, This paper is a written version of a one hour lecture given on Peter Shor's quantum factoring algorithm. 22 pages.

- Chapter 20 Quantum Computation, from Computational Complexity: A Modern Approach, Draft of a book: Dated January 2007, Comments welcome!, Sanjeev Arora and Boaz Barak, Princeton University.

- A Step Toward Quantum Computing: Entangling 10 Billion Particles, from "Discover Magazine", Dated January 19, 2011.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||